Human experience puts us on a winning path

In the first article of this series, it was established that there is an alternative to wholesale, long-term procurement transformation programs. Then, in the last article, we looked at how the adaptive approach can be applied to the people and organisation elements of procurement.

Previously we used the metaphor of a journey and the importance of arriving at the place you wanted to be.

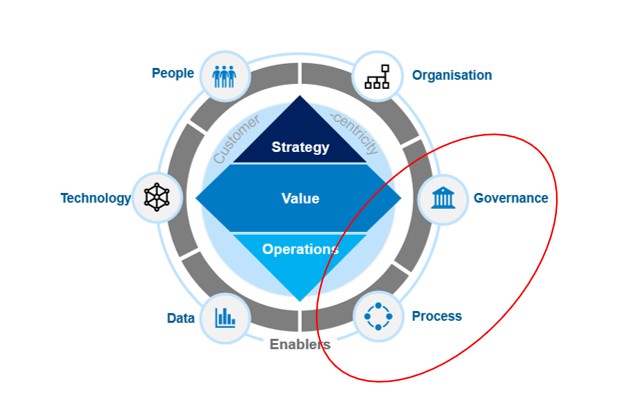

Now, as we turn our attention to the dimensions of process and governance – and how they might be considered within the adaptive model – we can again make use of the journey metaphor, but in a slightly different way.

Town planners talk about ‘paths of desire’. These are paths that the planners don’t create. Instead, people simply walk the way they want to, usually because it is a more common-sense way to go and is more often than not a shortcut. Typically, the town planners eventually catch up and formalise paths of desire where they can. We face much the same dynamic when it comes to process design.

Process design is a big deal mainly because we want a lot of people to use the processes, or to take the pathways we design. What’s more, we invariably have governance features and provisions applied to many processes, since the monitoring of processes is a major plank of good governance.

Source to contract (S2C); purchase to pay (P2P); supplier relationship management (SRM) and contract lifecycle management (CLM) are principal examples of processes linked to a procurement function.

When we get process design right everyone is happy. When we get it wrong, we get opposition, friction, and even deliberate non-compliance. Or, perhaps more correctly, we get people making paths of desire.

So, when we want to change processes, the traditional “major change” transformation approaches are high risk and can send us in the wrong direction and/or create processes that no one wants to use. The adaptive model is much safer.

The adaptive approach seeks to ensure that – instead of designing a fundamentally different model and embarking on a tortuous journey to get there – smaller, simpler and more flexible changes are tested and adopted. Changes that ensure you’re always in the right place, never heading in the wrong direction, and your people are happy to follow your new path.

Paying attention to human experience pays off

The last few years have seen something of a revolution in process design. Hallelujah! We are learning that, if humans are expected to use and adhere to a process, then it’s infinitely more likely they will stick to it if their experience is given primacy when conceiving the design. Think of it as if the town planners already know the path of desire – and incorporate it into their plan – because they use it themselves.

We are talking about human experience, or HX as the cool people refer to it. HX recognises that people are selective when it comes to choosing what to do and how to do it. It’s really quite important to design processes in a way that is likely to encourage these quirky, pernickety people to use the new process willingly. So, let’s make it easy for them to do the right thing.

Of the many causal factors that contribute to failures in business transformations, two of the most prevalent are technology failure (more on this in the next instalment) and user resistance.

Giving HX centre stage in process design itself represents an adaptive approach to change management. People find it easier to accept and embrace change if their experience is improved. Pure self-interest kicks in and they adapt because there’s something in it for them.

For most of us, we are more likely to buy into a change if:

- It’s incremental, as opposed to completely revolutionary

- It makes life easier, on balance

- The why and how are explained, in plain language, and

- It is easy because it’s intuitive and therefore easy to learn

In a procurement context, a common complaint of user or stakeholder communities is that the procurement function gets in the way. A genuine desire to overcome the chaos of many supplier relationships can cause the procurement team to be overzealous in their policing role when it comes to controlling spend and managing those supplier relationships.

By contrast, an HX-savvy function will carefully offset this control requirement with a more collaborative support and enablement counterbalance. The rule should be that we only get in the user’s way when absolutely necessary – and even then, only to make the outcomes even better for the internal client.

Automation needs to be embraced – just not in a robotic way

Increasingly we are also seeing the aforementioned quirky, pernickety people being replaced by digital technology as we progressively automate elements of the processes that lend themselves to such treatment.

Generative AI models such as ChatGPT-4, at the time of writing, need to be handled with an abundance of caution due to their ability to proffer, with supreme confidence, inaccurate information. However, over time wrinkles and errors will undoubtedly be ironed out as the models learn and mature.

Unquestionably, there’s a place for such automation in procurement processes and yes, they are inherently adaptive. Already it’s possible to start drafting RFP documents using generative AI (G-AI) tools and this frees up time for humans to undertake higher-value tasks.

Will the advent of G-AI make major changes easy to embed? Definitely. Is it a reality today? Not quite. The concepts and applications are still too nascent in this arena and there are still too few expert practitioners to describe it as a ubiquitous asset. But watch this space.

Good governance adds value too

Further to the “control versus enablement” point, most organisations recognise that it makes sense to implement controls, often involving very senior people’s intervention, around major procurement decisions. Unfortunately, to many stakeholders, these governance arrangements simply slow things down. They get in the way. They add little value.

This is because they were designed without keeping HX top of mind.

We implement straightforward and effective “sign-on, sign-off” procurement controls at many organisations and they absolutely can resolve these concerns about delays and lack of value.

What’s more, if well crafted, they also serve to auto-create, even “crash together”, effective multi-functional teams, early in the process. Then, they move with speed, don’t get bogged down, and bring stakeholders in on the journey to the extent that they concede this way to be better. The more senior the mandate the better.

Governance arrangements tend to be more onerous in highly regulated environments – such as the public sector and financial services. The smartest organisations find ways to work within the rules – often only marginally – in ways that still allow agility and creativity.

It’s amazing how two similar organisations, which are bound by the same rules and regulations, can implement drastically different internal processes and governance arrangements designed to ensure compliance. Those who opt for the heavy-duty approach are at a significant competitive disadvantage. They are expensive, they are slow and they are focusing their efforts in the wrong areas.

All heavily regulated businesses should take a good, critical look in the mirror. Overly heavy controls stifle the ability to adapt. Let’s be brave and remove the unnecessary approvals. Review delegated authority limits. Make compliance easy and beneficial. Build capability to capture and deal with non-compliance – albeit this becomes increasingly rare where compliance is simple and seen as helpful. We want our people to feel they are taking a path of desire rather than feeling they are being frogmarched.

Taking an adaptive approach to process design and good governance can be trusted. In the next article, we will look at technology and data as equally attractive candidates for adaptive approaches.